- Home

- Ron McCrea

Building Taliesin

Building Taliesin Read online

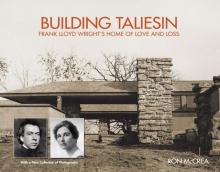

BUILDING TALIESIN

Rendering by Jim Mcintosh

BUILDING TALIESIN

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S HOME OF LOVE AND LOSS

RON McCREA

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

© 2012 by Ronald A. McCrea

E-book edition 2013

For permission to reuse material from Building Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home of Love and Loss, ISBN: 978-0-87020-606-1, please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

www.wisconsinhistory.org

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Society’s collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Front cover: Entrance to Taliesin construction site, 1911. Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society, all rights reserved.

Insets: Frank Lloyd Wright ca. 1906 and Mamah Bouton Borthwick ca. 1914. Photos courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ.

Designed by Earl J. Madden, M.F.A.

17 16 15 14 13 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

McCrea, Ron.

Building Taliesin : Frank Lloyd Wright’s home of love and loss / Ron McCrea.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-606-1 (pbk.)

1. Wright, Frank Lloyd, 1867–1959—Homes and haunts—Wisconsin—Spring Green. 2. Borthwick, Mamah Bouton, 1869–1914—Homes and haunts—Wisconsin—Spring Green. 3. Taliesin (Spring Green, Wis.) 4. Spring Green (Wis.)—Buildings, structures, etc. I. Title.

NA737.W7M365 2012

720.92—dc23

2012021754

This book is for Elaine

…and in memory of Robert LaBrasca (1943–1992), who knew I could.

CONTENTS

PREFACE ix

INTRODUCTION

TALIESIN I: LOST AND FOUND 1

Chapter 1 FROM TUSCANY TO TALIESIN 13

Chapter 2 “THE BELOVED VALLEY” 33

Chapter 3 BUILDING TALIESIN 59

LOST IMAGES AND LOVE LETTERS FROM THE “LOVE CASTLE”

Chapter 4 LIFE TOGETHER 121

Chapter 5 TRANSFORMATIONS 173

Acknowledgments 210

Illustration Credits 215

Index 217

PREFACE

Taliesin is a house in three acts.

In Act Three, Frank Lloyd Wright battles back from obscurity, marital strife, and financial reverses in the 1920s to become America’s first superstar architect. The artist born two years after the Civil War becomes a TV celebrity in the 1950s. Taliesin in Wisconsin becomes the home of Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship of apprentices and is the scene of lordly black-tie musicales.

In the second act—an act of complications—Taliesin is deserted while Wright is in Japan and California, then falls hostage to a jealous, deeply troubled wife. After a second fire, the estate is seized by the Bank of Wisconsin.

This book is about Act One. It begins with the decision of two people to risk everything for love and build a home for it, rises to a time of triumph—then ends suddenly in fire, murder, and Wright’s resolve to go on.

R.M.

BUILDING TALIESIN

INTRODUCTION

Fig. 1. It’s high summer at Taliesin in a photograph taken about 1913. A man and boy tend the garden bordering the carriage entrance while a young woman gathers flowers and a girl in knee-stockings stands with a horse. The photo was likely taken by a traveling photographer as a souvenir for sale with the oval mat as part of the print. The print is in an album belonging to the farm family. Photograph courtesy of Carla Wright.

TALIESIN I: LOST AND FOUND

In the fall of 1911 Mamah Bouton Borthwick wrote to her mentor, Ellen Key, at Strand, Key’s home in Sweden, to answer Key’s criticism of her love affair with Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright was a married man of 44 whose wife of 20 years would not grant him a divorce. Borthwick, 42, had divorced Edwin Cheney on August 8 after being married to him for 15 years.

“I have, as you hoped, ‘made a choice in harmony with my own soul’—the choice as far as my own life was concerned was made long since—that is absolute separation from Mr. Cheney,” she said. “A divorce was obtained last summer and my maiden name is now legally mine.

“Also I have since made ‘a choice in harmony with my own soul’ and what I believed to be Frank Wright’s happiness and am now keeping his house for him. In this very beautiful Hillside, as beautiful in its way as the country about Strand, he has been building a summer house, Taliesin, the combination of site and dwelling quite the most beautiful I have seen anyplace in the world. We are hoping to have some photographs to send you soon.

“Faithful comrade!

A dream in realization ended?

No, a woven, a golden thread in the human pattern of the precious fabric that is Life: her life, built into the house of Houses. As far as may be known—forever!”

Frank Lloyd Wright, 1932

“I believe it is a house founded on Ellen Key’s ideal of love. The nearest neighbor half a mile away is Frank’s sister [Jane Porter, at Tanyderi] where I visited when I first came here. She has championed our love most loyally, believing it her brother’s happiness.

“I have been thus far very busy with the unfinished house and because of the fact that workmen were boarded here in a nearby farmhouse, sometimes as many as 36 at a time. Mr. Wright’s sister has looked after this all summer but when I came it was turned over to me and I have done very little of your [translation] work in consequence of the building. The house is now, however, practically finished and my time again free.

Fig. 2. Frank Lloyd Wright, ca. 1906

Fig. 3. Mamah Bouton Borthwick, 1914

“Mr. Wright has his studio incorporated into the house and we both will be busy with our own work, with absolutely no outside interests on my part—my children I hope to have at times, but that cannot be just yet.”

Mamah’s description of their lives and plans in this remarkable letter is the fullest account yet of the early days of Taliesin, Wright’s estate at Spring Green, Wisconsin, which observed its 100th anniversary in 2011. The letter is the third of 10 discovered in Key’s archive at the Royal Library in Stockholm and brought to the world’s attention in 2002.1

Mamah apparently did send the photos she promised to Key, because in another letter, written around February 1912, she speaks of sending more. “I enclose two other views of the house,” she says. “The interior looks pretty bare, for there are no rugs yet nor many other things which will make it look more home-like.”

That description matches photographs in this book. The pictures of the living room and dining areas show “pretty bare” rooms without rugs or much decoration. These and other primitive photos of Taliesin were taken by Taylor A. Woolley.

THE FIRST PHOTOGRAPHER

Woolley, 26, was a draftsman who lived at Taliesin from mid-September 1911 through the spring of 1912 and took pictures the whole time. In Italy the previous year he and Borthwick had become friendly. He had lived with the couple in Fiesole above Florence while working on Wright’s two-volume Wasmuth Portfolio. Woolley also took photos in Fiesole. Some of them are included in these pages because Fiesole is where the idea of Taliesin took root.

“I have since made ‘a choice in harmony with my own soul’ and what I believed to be

Frank Wright’s happiness and am now keeping his house for him. In this very beautiful Hillside, as beautiful in its way as the country about Strand, he has been building a summer house, Taliesin, the combination of site and dwelling quite the most beautiful I have seen anyplace in the world. We are hoping to have some photographs to send you soon.”

—Mamah Bouton Borthwick to Ellen Key, 1911

Woolley’s collection of Taliesin photos—the first photos of the first Taliesin—has until now been scattered among three collections in historical societies and libraries in Wisconsin and in Utah, where Woolley was born and spent most of his career. The most important collection, a file of 58 negatives at the Utah State Historical Society that sat unnoticed, possibly for decades, and was not processed until 2002, contains rare views of Taliesin under construction. Additional photo prints from the series by Woolley found their way into the collection of his lifelong friend, partner in architecture, and brother-in-law, Clifford P. Evans, at the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah. Evans also was at Taliesin in the fall of 1911 and appears in several Woolley photos. He was 22.

The third portion of Woolley’s photographs is contained in an album once owned by a Spring Green couple and acquired on eBay by the Wisconsin Historical Society in 2005 for $28,200 after an intense fund-raising campaign. In a write-up in the New York Times the album was hailed as “a Rosetta Stone for the building” but its creator was a mystery. I have discovered that 21 of its 35 images are exact matches to Woolley negatives in Utah, including all three photos that make up the triptych of the living room, the album’s signature display. It can now be said with high confidence that Woolley was the photographer.

Woolley’s photographs not only match Mamah’s words, they match Wright’s own recollections of the first Taliesin summer and the craftsmen on the site. In them we see carpenters, stonemasons, and foremen of the sort who Wright remembers by name. We see chalk lines being laid down in a grid on Taliesin’s northeast slope to prepare for the vegetable gardens that Wright croons about in his chronicle.

Woolley left Taliesin in the summer of 1912 to be with his ailing mother. In a letter dated July 10, 1912, Wright tells Woolley to “take your time, enjoy yourself” in Utah, and notes: “All well here—the place quite transformed.”2

Mamah echoes this impression—that Taliesin has been transformed—in a letter to Key dated November 12, 1912. She says: “The place here is very lovely; all summer we had excursion parties come here to see the house and grounds, including Sunday-schools, Normal School classes, etc. I will try to send you some new photographs—you will scarcely recognize them from the others.”3

Both kinds of photos are represented in this book—the early, rough ones by Woolley (“the others”) and the “new photographs,” taken in the late summer of 1912 by Clarence Fuermann of Henry Fuermann and Sons, professional photographers from Chicago. Wright needed a polished portrait of Taliesin to illustrate his achievement in the January 1913 Architectural Record. A second illustrated article appeared a month later in Western Architect. In an introduction, the editors of Western Architect confess that photos cannot do Taliesin justice.

“Wonderfully situated on a site commanding every view of one of Southern Wisconsin’s most beautiful valleys is Taliesin, the country home of Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect” they say. “Photographs giving an adequate conception of the layout of the house and grounds with their beautiful surroundings are impossible to procure. Here and there the photographer is able to secure charming little details … but the Architect’s drawings themselves show more comprehensively the beautiful and artistic arrangement of this estate as planned by Mr. Wright himself.”4

Fig. 4. Olgivanna Lloyd Wright (photographed in 1949 at age 51) was the heroine of Frank Lloyd Wright’s late career, helping him through hard times and organizing the Taliesin Fellowship.

In February of 2011 a previously unknown collection of 25 photographic proofs of Fuermann’s Taliesin set, plus a few other unidentified images, was put up for sale on eBay and acquired by the Wisconsin Historical Society. They became available in time for a selection of them to be included in this book. These beautiful photos, some never published, show Taliesin at its peak, with its gardens, stone steps, and Tea Circle fully formed, its courtyards in bloom, and its vegetable gardens popping with cabbages and other crops, ready for the first harvest.

THE LADY VANISHES

One Fuermann photo shows a horse and two young people under the portecochere, as seen from the hill garden. The next photo presented here, taken two years later by an anonymous photographer from the same perspective, is horrifying. It shows Taliesin in smoking ruins, the porte cochere crashed to the ground. If the two young people in the previous photo were the Cheney children, John and Martha, they are now dead, killed with their mother while having lunch on Saturday, August 15, 1914, during their annual summer visit.

The mass murder and fire claimed seven lives and eventually the life of Julian Carlton, the killer from Chicago. Perversely, it claimed both the life and the identity of the woman for whom Taliesin was built.

Wright in his autobiography is able to remember and recite the names of carpenters, stonemasons, and foremen who worked on the construction site. He is even able to quote them. But he is not able to name the woman who cooked for the crew and was Taliesin’s reason for being.

In fact, Wright never names Mamah in An Autobiography except for one first-name reference in the first edition and two in the second. He names all his other wives—Catherine Tobin Wright, Miriam Noel Wright, and Olgivanna Lloyd Wright—the last two of whom were also mistresses before they were wives—and even Zona Gale, the Pulitzer Prize—winning dramatist whom he courted but who rejected him.

But references to Mamah are elliptical.

She is “her who, by force of rebellion, as by force of Love, was then implicated with me.”

She is “the best of companionship” (though her companionship is omitted from his account of their 1913 trip to Japan).

She is “a kindred spirit” at Taliesin, “a woman who had taken refuge there for life.”

In the discussion of her death, she is “she for whom Taliesin had first taken form.”

But she is never Mamah Borthwick.

In a coda to the tender account of their sojourn in Tuscany in 1910, Wright exclaims: “Faithful comrade! A dream in realization ended? No, a woven, a golden thread in the human pattern of the precious fabric that is Life: her life, built into the house of Houses. As far as may be known—forever!” He is saying that Mamah’s spirit always animated Taliesin and always will. But he cannot utter her name.5

It was not always so. Five days after she was killed, Wright names Mamah five times in an open letter to his neighbors. After thanking them for their kindness, he fires a parting shot at married critics: “You wives with your certificates of loving—pray that you may love as much and be loved as well as Mamah Borthwick!”6

Immediately after her death, then, she is still a real woman, an individual with a history. But in Wright’s 1932 autobiography she is a ghost. She has become, in the words of Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, “an almost ephemeral, mythical figure, too close, too precious, to be able to describe. He does not even mention her name.”7

There are many reasonable explanations as to why Wright did this, but the net result is that in his memoir the first lady of Taliesin has vanished.

CREATIVE TOGETHER

The creative legacy of the original Taliesin was also pushed into obscurity almost immediately after the fire. It was forgotten that during their brief years together Wright and Borthwick were a powerhouse of production.

Between 1911 and 1914 Wright developed a new design vocabulary and his talent flowered in some of his most distinctive works. They started with Taliesin itself and included the Avery Coonley Playhouse, with its famous balloons-and-confetti “kindersymphony” windows; the Francis Little House, whose tawny living room is now installed in the American Wing of the Metr

opolitan Museum of Art; and Midway Gardens, a modernist fantasy of buildings, restaurants, and an outdoor concert garden that occupied a full city block in Chicago.

Wright also opened a second career as a major collector and dealer in Japanese art, taking Mamah to Japan with him in 1913, purchasing thousands of

Frank Lloyd Wright had been lost to a generation, a critic for the Los Angeles Times observed in 1988, speaking of “the dark ages for Wright designs, which preceded his death in 1959 and spanned the following generation.” Tastes in modern design had shifted to Bauhaus and Scandinavian styles.

artworks, and landing the contract to build the new Imperial Hotel for the Imperial Household in Tokyo. He published The Japanese Print: An Interpretation in 1912, while still promoting U.S. sales of his two-volume Studies and Executed Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, which had taken Europe by storm.

Wright and Borthwick became publishing partners in the effort to spread the gospel of women’s liberation and marriage-law reform being promoted by the popular Swedish philosopher-activist Ellen Key. With Borthwick working as her official American translator and Wright handling publishing contacts and financing, they published three books through Wright’s Chicago publisher, Ralph Fletcher Seymour. Mamah’s translation of The Woman Movement was issued by Putnam’s in New York with an introduction by Havelock Ellis. A final translation, Key’s profile of the French peace acvitist Romain Rolland, was published in 1915 in Margaret Anderson’s experimental Chicago-based Little Review, which Wright had helped get started with a $100 donation.

Fig. 5. Robert Orth, appearing in the role of Frank Lloyd Wright, sings a love duet with Brenda Harris, portraying Mamah Borthwick Cheney in the Chicago Opera Theater’s 1997 revival of the Daron Hagen opera Shining Brow. The opera premiered with the Madison Opera in 1993 and has had other revival performances in Florida, Nevada, and Buffalo, New York.

Building Taliesin

Building Taliesin