- Home

- Ron McCrea

Building Taliesin Page 10

Building Taliesin Read online

Page 10

That William stayed with Taliesin through trials and tribulations the better part of 14 years. America turns up a good mechanic around in country places every so often. Billy was one of them.

Winter came. A bitter one. The roof was on, plastering done, windows in, the men working inside. Evenings, the men grouped around the open fireplaces, throwing cordwood into them to keep themselves warm as the wind came up through the floorboards. All came to work from surrounding towns and had to be fed and bedded on the place during the week. Saturday nights they went home with money for the week’s work in pocket, or its equivalent in groceries and fixings from the village.

Their reactions were picturesque. There was Johnnie Vaughn, who was, I guess, a genius. I got him because he had gone into some sort of concrete business with another Irishman for partner, and failed. Johnnie said, “We didn’t fail sooner because we didn’t have more business.” I overheard this lank genius [while] he was looking over the carpenters, nagging little Billy Little, who had been foreman of several jobs in the city for me. Said Johnnie, “I built this place here off a shingle.” “Huh,” said Billy, “that ain’t nothin’. I built them places in Oak Park right off ’d air.” No one ever got even, a little, over the rat-like perspicacity of that little Billy Little. Workmen never have enough drawings or explanations no matter how many they get—but this is the sort of slander an architect needs to get occasionally.

The workmen took the work as a sort of adventure. It was an adventure. In every realm. Especially in the financial realm. I kept working all the while to make the money come. It did. And we kept on inside with plenty of clean soft wood that could be left alone, pretty much, in plain surfaces. The stone, too, strong and protective inside, spoke for itself in certain piers, and walls.

Inside floors, like the outside floors, were stone-paved or if not were laid with wide, dark-streaked cypress boards. The plaster in the walls was mixed with raw sienna in the box. Went onto the walls “natural,” drying out tawny gold. Outside, the plastered walls were the same but grayer with cement. But in the constitution of the whole, in the way the walls rose from the plan and the spaces were roofed over, was the chief interest of the whole house. The whole was all supremely natural. The rooms went up into the roof tent-like, and were banded overhead with marking strips of waxed, soft wood. The house was set so sun came through the openings into every room sometime during the day. Walls opened everywhere to views as the windows swung out above the treetops, the tops of red, white and black oaks and wild cherry trees festooned with wild grapevines. In spring, the perfume of the blossoms came full through the windows, the birds singing there the while, from sunrise to sunset—all but the several white months of winter.

I wanted a home where icicles by invitation might beautify the eaves. So there were no gutters. And when the snow piled deep on the roofs and lay drifted in the courts, icicles came to hand staccato from the eaves. Prismatic crystal in pendants sometimes six feet long glittered between the landscape and the eyes inside. Taliesin in winter was a frosted palace and walled with snow, hung with iridescent fringes, the plate glass of the windows delicately fantastic with frosted arabesques. A thing of winter beauty. But the windows shone bright and warm through it all as the light of the huge fireplaces lit them from the firesides within and streams of wood-smoke from a dozen such places went straight up toward the stars.

The furnishings inside were simple and temperate. Thin tan-colored flax rugs covered the floors, later abandoned for the severer simplicity of the stone pavements and wide boards. Doors and windows were hung with modest, brown checkered fabrics. The furniture was “home-made” of the same good wood as the trim and mostly fitted into the trim. I got a compliment on this from old Dan Davis a right and “savin’” Welsh neighbor, who saw we had made it ourselves. “Gosh-dang it, Frank,” he said, “Ye’re savin’ too, ain’t ye?” Although Mother Williams, another neighbor, who came to work for me, said “Savin’? He’s nothin’ of the sort. He could ’ave got it most as cheap ready-made from that Sears and Roebuck … I know.”

A house of the North. The whole was low, wide, and snug, a broad shelter seeking fellowship with its surroundings. A house that could open to the breezes of summer and become like an open camp if need be. With spring came music on the roofs for there were few dead roof-spaces overhead, and the broad eaves so sheltered the windows that they were safely left open to the sweeping, soft air of the rain. Taliesin was grateful for care. Took what grooming it got with gratitude and repaid it all with interest.

Taliesin’s order was such that when all was clean and in place its countenance beamed, wore a happy smile of well-being and welcome for all.

It was intensely human, I believe.

An Autobiography, 222–229. Reprinted with permission of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, all rights reserved.

NOTES

1. Heather Oswald, visual resources and archives manager of the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Research Center, says the center has a record that “a nephew of Catherine Tobin Wright recalled the theater from his visits. We do have notations that Llewellyn mentioned it as well; however, there is no primary source on this… . We have no record of what became of it.” email to author, July 12, 2010.

2. Richard Hovey, “Taliesin: A Masque,” in Poet-Lore, A Monthly Magazine of Letters, (February, 1896), 71. The author is grateful to Anthony Alofsin for his article “Taliesin: ‘To Fashion Worlds in Little,” which included Wright’s rendering of the puppet theater and the 1914 photo at the Chicago Art Institute. Without these aids, seeing the theater in place at Taliesin would have been a puzzle. See Wright Studies Volume One: Taliesin 1911–1914, Narciso Menocal, ed., Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press (1992), 47–49.

3. Elizabeth Catherine Wright, e-mail to author, September 29, 2010. The letter she refers to is Robert Llewellyn Wright’s “Letters to His Children on His Childhood,” undated typescript. The Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Research Center has a reference copy. Elizabeth Wright’s memoir of her parents and their correspondence, Dear Bob, Dear Betty: Love and Marriage During the Great Depression, privately published in 2009, is available at the Taliesin Bookstore.

4. Tim K. Wright, e-mail to author, November 13, 2011.

5. Robert Llewellyn Wright to Frank Lloyd Wright, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona, used by permission.

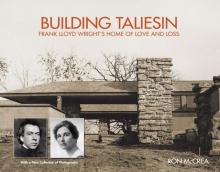

LOST IMAGES AND LOVE LETTERS FROM THE “LOVE CASTLE”

Author’s note: One year after Building Taliesin was published, a new album of Taylor Woolley’s Taliesin photographs taken in 1911 and 1912 came to my attention, along with two remarkable letters written from Taliesin in the first months of 1912. The album originally belonged to George Emanuel Elgh (1891–1954), who lived and worked with Woolley and Clifford Evans in the drafting quarters at Taliesin. The album contains 35 images, nearly all of which appear in this book, drawn from other collections. Six of them, however, have not been seen before. They are published for the first time here, along with the letters, thanks to the generosity of Elgh’s family and of Christopher Vernon, the Australian scholar who discovered them.

The letters were written during a bitterly cold Wisconsin winter by 20-year-old George Elgh to his future wife, Nellie Elizabeth Anderson, then 18 and living in Chicago.1 Charming and heartsick, the letters contain vivid descriptions of life and work at Frank Lloyd Wright’s rural refuge, which Chicago newspapers were calling the “Love Castle” in its first controversial months.

Two years later, George and Nellie Elgh set off for Melbourne, Australia, on June 29, 1914, just two days after they were married in Chicago. There he joined former Oak Park architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin in the grand enterprise of planning and designing the new national capital city of Canberra. Three years later the Elghs returned to the United States and settled in suburban Chicago, where George spent the rest of his career working as a draftsman.

While trying to learn more about this little-known associat

e of the Griffins, Vernon, an associate professor in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia, discovered Elgh’s Taliesin album and love letters in Illinois. Professor Vernon volunteered the rare materials to be added to this digital edition of Building Taliesin, and the Elgh descendants approved.2 I am deeply grateful to both, and believe that readers will be also.

Ron McCrea

Madison, Wisconsin

July 21, 2013

January 14, 1912: “Now to tell you of the dandy place that I am in”

Overview: George Elgh has come to work at Taliesin on a tryout. Writing on a Sunday, he tells Nellie that if he passes his probation in the next week, she won’t see him for a month. Wright allows his draftsmen just one free weekend. (In his next letter, Elgh has passed the test.) George worries that he and “dearest friend Nell” will grow apart, begs her to write at least once a week, and assures her that “Mr. Wright is a very fine man” who will allow him to come home “if anything goes wrong and you get sick abed.”

He describes his arrival in Spring Green and his reception by Wright, who meets his train in a horse-drawn sleigh and takes him to dinner. George gives Nellie a detailed description of Taliesin and its surroundings. He assures her that his new home is a “dandy place” with impressive creature comforts, including radiant heat, hot and cold running water, and plenty to eat. He loves the drafting room, though not Taylor Woolley’s habit of playing opera recordings while they work—the first description of music in the working life of Taliesin. For recreation, George goes tobogganing with a workman on the hills of Jones Valley.

Nellie appears to be aware of the scandal surrounding Taliesin that had broken in the Chicago newspapers over the Christmas holidays, when it was revealed that Wright, 44, and Mamah Borthwick, 42, had left their families and were living together unmarried in a Wisconsin hillside hideaway. George, who refers to Mamah Borthwick as “the Mrs,” tries to address Nellie’s concerns. “Now don’t believe that this place I am in is bad as the Chicago American [a Hearst daily] says it is because it is not,” he assures her, “and when I get home I will tell you all about it if you wish to hear.”

Because Wright is particular about his mail and likely to throw out postcards, Elgh instructs Nellie to use stamped envelopes and address her letters to the care of Frank Lloyd Wright, “not F.L.”

The Elgh letters are published here unedited except for some clarifications in brackets.

* * *

Spring Green Wis

Jan 14, 1912. Snowing

Dearest friend Nell:-

Well sweetheart I hate to let you hear the bad news That is if I am not home next Sunday I will not be home for four long weeks. It all depends upon whether I make good. In case I don’t you will see me as often as of old and will get tired of me (perhaps). Otherwise I will be home Saturday afternoon and Sunday every four weeks. But never mind Nell, just remember that I am thinking of you every day and will look forward to the few days or rather one that I will be with you. Uncle Sam will keep us near each other, won’t he Of course he will.

Well Nell it took me 21½ hrs from the time I left home until I was at my destination. You heard about the first part of it (my trip) Well the second part was worse. It over 3 hrs to come [40 miles] from Madison to Spring Green. And at every stop we had to wait from 10 to 20 minutes for the engine to get up steam and the cars were cold as could be 32 above. I was met at the station by Mr. Wright bundled up so that all you could see was his eyes. We had dinner in town and then drove to Mr. Wright’s place 2½ miles away in a double seated sleigh drawn by a team of spirited horses

The town of Spring Green is a pretty lively place and of pretty good size, but it is so far away that I am afraid I won’t get there very often as it gets awfully cold up here and the snow is from 4” to 12” deep all over.

Now to tell you of the dandy place that I am in. The house is about 200 ft long with wings on all sides Mr. Wright and the Mrs live in one part of it and then there is a large covered porch between it and the draughting R’m which includes our quarters. First come the draughting room which is great It has Spencer & Powers place beat to a frazzle3 adjoining it is a long hall used as a filing room for drawings and on the north-west side of it, (I think that is it as I have not quite got my bearing as yet) is a porch. Next comes a reading room. And after that is the dormitory with four bunks not beds, two on each side of the room 1 over the other with a light for each bunk so a fellow can lay in bed and read. Did you say soft[?] Off the dormitory is a bath room complete with hot and cold water. There is a large fire place in the draughting room and one in the reading room. Both are real large and built of stone very rough. Beyond that is the garage and Stable

Now to let you know what kind of landscape we have up here. The house sets on the crest of a large hill about 150 ft high almost as high as the twelveth floor of Steinway hall.4 On all sides of us are hill from 100 to 300 feet high one after the other for miles and miles as far as you can see. You no sooner get down one then you start going up another, with trees by the thousands. The river is about a half a mile below us and is about a quarter of a mile wide at that point.

I was out tobogganing with one of the men this morning and we went to a hill about ½ mile away which is about 250 ft high. It was tough work climbing it but when you go down. Say the snow flies into your face you can’t see where you are going and hit the bumps at an awful speed. You can’t get your breath. The fellow I was with said we must have gone down the hill at about 50 to 60 miles an hour. We took three trips and I only wished we could take some more but the fellow I was with is about 50 or 55 years old and could not stand the climbing No doubt I will go out again this afternoon. And my only regret is that you are not here to enjoy it with me but never mind you must come up here when it gets warm that is if I stay and stay at least a week and I bet you will enjoy it. It is a much nicer place than Mr. Warrens at Lakeside. I just saw a robin about 15 minutes ago and I heard several this morning and also some Blue jays. The place is nice and warm as we have hot water heat with a Rad.[iator] In each room. The light is ascetylene gas, which is better than Electric light as it burns with an even white light.

You will have to excuse spellings and so forth as I am bad enough at that without haveng to listen to a Victrola playing Grand opera. Which is in the draughting room at the request of Mr. Wooley the head draughtsman. Now don’t believe that this place I am in is bad as the Chicago American says it is because it is not and when I get home I will tell you all about it if you wish to hear.5

The meals I get up here are very good with plenty of fresh milk to drink and all you want to eat.

Well Nell, don’t get angry at me because I took a job so far away from home and you, but you know it is for my good and I certainly am sacrificing an awful lot by being up here but then if anything goes wrong and you get sick abed, seriously, I will come right a way as Mr. Wright is a very fine man and would let me go to Chi if I let him know. I prayed to the Lord to take care of my friends and you especially and I know He will. And I am going to pray for you every day. Remember you must let me know because nobody else would. I want to hear from you at least once a week and alway use a two cent Stamp as Mr. Wright does not pay much attension to post cards and you never know when you have received any Mail.

Well Nell, I think I have given you a good description of the place and I will close now and store up some more news.

With lots of love for yourself and best wishes to my other friends I remain

Your loving friend

George

Address

Spring Green Wis

% Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright

not F. L.

* * *

February 4, 1912: “I am allway feeling tired”

Overview: Writing three Sundays later, Elgh has had a taste of life at Taliesin. The bloom is off the rose, and he can’t wait to get back to Chicago for his first leave in one week. He tells Nellie that there i

s drafting work at Taliesin that would take six people more than a year to finish, but there are only “three draughtsmen on the job”—him, Taylor Woolley, and, presumably, Woolley’s partner Clifford Evans. Wright has made a fresh start in his studio by hiring three men in their 20s. Elgh is 20, Evans 22. Woolley, 27, is “the head man here.”

Elgh is religious and apparently the only teetotaler among the staff. He writes of walking to town with the two draftsmen and a carpenter. “The other fellows were going to town to fill up as usual,” he says. And: “I got discusted reading the Bible to fellows that come in and oderize the room with the fums of whisky. I do know that is the time to read to them but you know how it is.” Woolley and Evans were non-observant Mormons from Salt Lake City. Wright did not drink and the Lloyd Jones clan of Taliesin’s environs were temperance crusaders. George drinks six to eight glasses of fresh milk each day, but says the coffee is bad because “the cook is no good.”

Nellie, still following the scandal at Taliesin, appears to have asked if the picture on a postcard George has sent her is of the “Love Castle,” one of several steamy sobriquets that Chicago headline writers have given to Taliesin. George explains that it is Hillside Home School.6 “That card I sent you was not a picture of the Love Castle but a photo of one of the buildings that belong to the private school for girls and boys from 5 to 20 years old. Mr. Wright was the archi choke for it.” He means architect; his little joke.

George worries about a sick mutual friend, and about hearing from Nellie that “everyone was angry that I had not written.” “The next five days will seem like five weeks,” he tells his fiancée.

Building Taliesin

Building Taliesin