- Home

- Ron McCrea

Building Taliesin Page 12

Building Taliesin Read online

Page 12

Wright paces back and forth in the living room of “the bungalow which he has built on the great limestone crag which commands a view of the Wisconsin River and miles of the valley.” Then he lays it all out.

ON HIS MARRIAGE: Wright says his marriage to Catherine when she was 19 and he was 21 was “a mistake” that became “a tragedy.” “Mrs. Wright wanted children, loved children, and understood children. She had her life in them. She played with children and enjoyed them, but I found my life in my work. … In a way my buildings are my children.”

ON MAMAH BORTHWICK: Catherine “did not understand my going away. She does not understand it now. She thinks I am infatuated with another woman. That isn’t the whole of it. I went away because I found my life confused and my situation discordant. … I have been trying to live honestly. I have been living honestly. Mrs. E.H. Cheney never existed for me. She was always Mamah Borthwick to me, an individual separate and distinct, who was not any man’s possession.”

ON CHILD SUPPORT: “Everything I have done up to this time is at their disposal. I have taken nothing and shall take nothing from them. My earning capacity means a much and is as rightly at their service as ever.”

ON LOSING WORK: “It may be that this thing will result in taking my work away from me. … an architect comes into intimate contact with his client as does a physician. He consults the wishes of a family about a home. There will be people who will be unwilling to have me in that intimate relation. It will be a waste of something socially precious if this thing robs me of my work. I have struggled to express something real in American architecture. I have something to give. It will be a misfortune if the world decides not to receive what I have to give.”

“Two trunks are packed in the main hall and a fast team is standing harnessed in the barn. … Wright has a complete spy system. He will be informed the instant that Sheriff Pengally leaves Dodgeville.”

Carbondale (Ill.) Free Press, December 29, 1911

ON SELFISHNESS: “If I could have put aside my desire to live my life as I build my buildings—from within outward—I might have been able to stay. But … I wanted to be what I had come to feel for some years that I was. I would be honestly myself first and take care of everything else afterward.”

ON RULES FOR GENIUSES: “I want to say this: Laws and rules are made for the average. The ordinary man cannot live without rules to guide his conduct. It is infinitely more difficult to live without rules, but that is what the really honest, sincere, thinking man is compelled to do. And I think when a man has displayed some of his ability to see and feel the higher and better things of life, we ought to go slow in deciding he has acted badly.”

TRUTH—AND CONSEQUENCES?

The truth was out. Now, would there be consequences? The press hoped there would be. Starting the day after Christmas, stories began to appear reporting that local citizens were up in arms and law enforcement officials were being pressed to act. There was talk of tar and feathers.4

“Neighbors of Frank Lloyd Wright decided this afternoon that if their disapproval was nothing to him they would find more effective means of compelling him to abandon his plan of making his hilltop bungalow a permanent home for himself and Mamah Borthwick, who, until her divorce was Mrs. E.H. Cheney,” the Tribune reported on December 26. “They appealed to Sheriff W.R. Pengally of Iowa County to help them.”

“The citizens who consulted me do not want to take the law into their own hands,” Pengally allegedly responded. “I told them I would thwart any attempt at tarring and feathering. I don’t believe Wright’s neighbors intended to do anything of the sort. They want him to leave and they think he can be compelled to go by legal means or else send away this woman he is reported to be living with.”5

Nevertheless, a United Press story in the Des Moines News announced: “Tar and Feathers for Wright and Soulmate.”6

“TAR PARTY” AT “LIMESTONE GROTTO”

The stories grew more bizarre with distance, as wire services and syndicates carried versions of reportage that first appeared in Chicago papers.

The syracuse, N.Y., Herald’s headlines on December 26 said: “Elopers Guarded from College Boys / Sheriff Stations Sentries at $10,000 ‘Cave.’ / Tar Party Threatened / Architect Who Deserts Wife and Six Children to Live With His Charmer in Limestone Grotto Enrages Residents of Hillside.”7

“Wright has refused all callers the privilege of seeing Mamah and insists upon receiving his visitors in his workshop or study. The mystery suite where the affinities live is closed and barred to the world. There is no window … a glimpse of the interior is impossible.”

Fairbanks (Alaska) Citizen, February 12, 1912

The story, datelined Chicago, said: “A guard was today placed around the $10,000 limestone grotto, or cave, of Frank Lloyd Wright, architect, at Hillside, Wis., where he is living with Mamah Borthwick, while his own wife and children wait for him in Oak Park, a fashionable suburb.

“Threats of tar and feathers moved the Sheriff to take the precaution of placing a guard. … The population of Hillside is made up largely of college students, and the sheriff says they are apt to ‘bust out any minute.’

“The only thing that has prevented a tar party so far,’ said sheriff Brown [sic], ‘is the lack of a leader. There has been plenty of talk of such action both here and in Spring Green. But no one seems willing to suggest the actual plans.’”

The next day’s Herald announced that at 10 a.m., the Iowa County sheriff had led a posse out of Dodgeville, “determined to raid Frank Lloyd Wright’s ‘Castle of Love.’”8 The following day, the Herald reported that although “an attempt yesterday to break up the combination was unsuccessful, the arrest of the esthetic architect and his ‘art mate’ is imminent.” But, it still might not happen until “after the ‘Love Castle’ has been besieged and captured by force of arms.”9

MAKING UP MAMAH

The silence of Mamah Borthwick was frustrating, so reporters began to fill in the blanks.

“Mrs. Borthwick, in a merry mood, chaffed the reporters, declaring she was sorry for them,” said a wire story in the Racine Daily Journal. “‘It’s a pity they have sent all you fellows up here just to watch me,’ she allegedly said. “‘We are bothering no one and want only to live our lives in peace.’” She then allegedly referred all “questions about soulmating and spiritual love” to Wright, but “declared she would ‘stick to him.’”10

Another story had Mamah personally keeping tabs on the press corps. “Every movement made by the small army of newspaper correspondents is at once reported to the bungalow by telephone,” it said. “The former Mrs. Cheney receives many of the communications and displays the liveliest interest.”11

Other stories had her locked away. In Fairbanks, Alaska, the news on February 12, 1912 (datelined January 7) was that Wright was holding Mamah in “the inner room of his ‘Castle of Spiritual Love.’” The headline was, “Barred doors Hold Soulmade [sic] Prisoner.”12

“Wright has refused all callers the privilege of seeing Mamah and insists upon receiving his visitors in his workshop or study,” the story said. “The mystery suite where the affinities live is closed and barred to the world. There is no window … a glimpse of the interior is impossible.”

In a burst of histrionics, the reporter laments: “The real Mamah, the Mamah of Port Huron, the Mamah of ‘the good old times in Oak Park,’ the Mamah for whom her children are crying and praying, is as much a mystery as the chamber where she spends her hours in solitude or with her twentieth-century champion of marital freedom.”

FAST HORSES AT THE READY

As the saga neared its end, readers of the Carbondale Daily Free Press in Illinois were told that Frank and Mamah were about to make a run for the border. “The belief grows stronger that plans for flight have been matured at the ‘love bug’ bungalow. Two trunks are packed in the main hall and a fast team is standing harnessed in the barn. …

“You understand of course that everything would be condo

ned by the public if only we were married. But Frank of course cannot marry as he has not been divorced. Neither of us has ever felt, of course, that that had the slightest possible significance in the ‘morality’ or ‘immorality’ of our action, but it has all the significance in the newspaper-public consciousness.”

—Mamah Borthwick to Ellen Key, ca. February 1912

“It is believed that Wright and his affinity plan to slip away by the east road from that on which the sheriff approaches and to evade arrest by reaching Illinois before a warrant can be served. Wright has a complete spy system. He will be informed the instant that Sheriff Pengally leaves Dodgeville.”13

“I REFUSE TO BE THE GOAT”

Fanciful reports like these made Pengally increasingly impatient. On December 29, pestered by reporters, he told the Tribune: “There’s nothing doing. I haven’t seen any complaint and I am not going to monkey with this business until I do.”14 The next day, when pressed again, he fumed, “I refuse to be the goat in this affair.”15

Wright issued a statement: “We are here to stay. The report that the people of Spring Green are preparing to make a raid on us has no foundation in fact. I have received no notice from any law officer of the county and I do not expect to.”16

He was right. Nothing happened. The story petered out in ten days and the reporters went home.

A DEFENSE FROM CHICAGO

At the height of the fever, when it appeared that Wright and Borthwick were in danger of arrest, they received a strong and unexpected defense from an important voice in Chicago. Floyd Dell, just 24, had risen to be the editor of the Chicago Evening Post Friday Literary Review. But Dell was more than that: he was the leader of the community of artists and writers known as the Chicago Renaissance.

Wright’s publisher, Ralph Fletcher Seymour, had just released Mamah Borthwick’s first volume of Ellen Key translations, The Morality of Women. Dell gave the book his lead review in the Literary Review of December 29, taking direct aim at the campaign being waged against the couple.

Dell notes that Key maintains that a legitimate marriage should be defined by love, not law. He quotes her as saying, “This love, legally sanctioned or not, is moral, and where it is lacking on either side a moral ground is furnished for the dissolution of the relationship.”

Dell demurs: “In this country the matter of law is more exigent. It is seldom dispensed with except when, on account of our too rigid laws, it is impossible to secure it. Those who try to realize their ideal under such circumstances must be very strong or very cunning, or else very insignificant, to succeed.

“A case very much to the point is that of the translator of this book, Miss Namah [sic] Borthwick, who, as the result of attempting to put its ideas into practice openly, and thus avoid the soul-corroding poison of secrecy and hypocrisy, is at the present time being hunted and harried by newspapers and officers of the law; while the man who has joined with her in this attempt, a first-rate artist, stands in danger of having a career of great social value brought to ruin. The difference between America and Europe—a difference by no means to our credit—is shown in the vicious fanaticism with which we attack an attempt made obviously in good faith.”

Dell concludes, sharply: “Let us not be under the illusion that the ideal of monogamy can be implanted in people’s hearts by sheriff’s posses.”17

Mamah, whose first name is misspelled on the title page of the book’s early editions in the review, appreciated the article enough to share it with Ellen Key. In an undated letter sent from Taliesin to Sweden with the clipping, she notes: “The reference of Mr. Floyd Dell in the ‘Post’ is to the unpleasant publicity the ‘Yellow Journals’ gave to our situation here. They fabricated and published interviews and occurrences which, of course, never took place. The ‘officers of the law’ was one of these fictions. You fortunately have nothing in Europe like our ‘Yellow Journals,’ which go to any length to print something they can print as sensational.”

She adds: “You understand of course that everything would be condoned by the public if only we were married. But Frank of course cannot marry as he has not been divorced. Neither of us has ever felt, of course, that that had the slightest possible significance in the ‘morality’ or ‘immorality’ of our action, but it has all the significance in the newspaper-public consciousness.”18

“RATHER WITLESS AND MORE OR LESS INCREDIBLE TALES”

One small Wisconsin newspaper cut through the fictions and turned the spotlight on the visiting press. A Dodgeville Chronicle headline on January 5, 1912, said: “Public Craving for Sensation Basis for Much Buncombe.“ Buncombe is another spelling of bunkum. Bunkum is another name for bunk.

The story, likely the work of editor John M. Reese, described the circus that followed the revelation that Wright and Borthwick were living together:

“Since the matter came up, Spring Green, about three miles distant from the Wright habitation, has become the headquarters for a small army of reporters and photographers, and the local telegraph office has taken on an added importance with the stationing there of an extra operator.

“To some of these reporters Wright has accorded interviews, and has through them given out a lengthy statement of the situation from his standpoint. Villagers, while the Wright case is the great subject of conversation, seem inclined to side with Wright in his resentment toward some of the reporters, whose conduct during their enforced isolation and idleness has been of a character to force public sympathy in that direction.

“One reporter, when asked with regard to the matter, stated that the furore with regard to this case was prompted by the prominence of the parties concerned and the desire on the part of the newspapers to gratify the public craving for sensation.

“The tiresome waiting for developments that do not materialize, and the desire to justify their presence here by accomplishment, must be in a measure responsible for the rather witless and more or less incredible tales of local excitement, indignation meetings, hints of violence, and such like matter published in the daily papers, as well as the besieging of county officials with queries and suggestions of actions.

“Particularly Wright has avoided and frustrated the photographers … In his protection of himself and grounds from the camera men and reporters Wright has several men employed, and when, by his direction on a recent occasion one of them grappled with a photographer to prevent his getting a focus on Wright, the act was applauded by onlookers, including village officials, and mutters against the ‘fresh Chicago guys,’ all indicating the state of mind in that locality with regard to this eccentric character.”19

Fig. 109. Floyd Dell, age 27, in a 1914 portrait by John Sloan.

“A case very much to the point is that of the translator of this book, Miss Namah [sic] Borthwick, who, as the result of attempting to put its ideas into practice openly, and thus avoid the soul-corroding poison of secrecy and hypocrisy, is at the present time being hunted and harried by newspapers and officers of the law; while the man who has joined with her in this attempt, a first-rate artist, stands in danger of having a career of great social value brought to ruin.

“The difference between America and Europe—a difference by no means to our credit—is shown in the vicious fanaticism with which we attack an attempt made obviously in good faith. … Let us not be under the illusion that the ideal of monogamy can be implanted in people’s hearts by sheriff’s posses.”

—FLOYD DELL, Chicago Evening Post Friday Literary Review, December 29, 1911

Fg. 110. The living room of Northome, the Minnesota summer home of Francis and Mary Little, is installed in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The home was built from 1911 to 1914 in a high Prairie style, with extra size and high ceilings in the living room so that Mary Little could hold piano recitals.

WRIGHT AT WORK, 1911–1914

The storm that buffeted Taliesin turned out to be a squall. It blew its way through the valley and was over. Frank Lloyd Wright and Mama

h Borthwick scarcely missed a beat before settling into the life they had fought to live.

“We work together,” Wright told Francis and Mary Little, his Minnesota clients. Their creative collaboration lasted just three years before Taliesin was destroyed and Mamah was killed. But it was a productive time.

Beginning with Taliesin, Wright produced some of his finest architecture. His masterworks, like Taliesin, were self-contained worlds: the walled Midway Gardens concert garden in Chicago; the enclosed Imperial Hotel plan for Tokyo; and the Coonley Playhouse, a small gem of a progressive school.

He opened a second career as a dealer in Japanese art, quickly rose to the top, and published a classic book on the topic, The Japanese Print. His efforts furnished some of America’s greatest museums with their collections of Japanese prints.

Mamah Borthwick translated four books by Ellen Key dealing with women’s rights, marriage and divorce reform, and female fulfillment. Wright was an active collaborator and underwriter. Together they fought obstacles to publication in Chicago and New York. They traveled together to Manhattan and Tokyo, and received luminaries at Taliesin.

These years, 1911–1914, are included among what Anthony Alofsin calls Wright’s “lost years.” They may have been lost to history for a time, but they were not lost to Wright and Borthwick. They were years in which the couple, in the prime of life, secured their home and pursued their dreams. Wright spread his wings in Europe and Asia and returned to Chicago trailing clouds of glory.

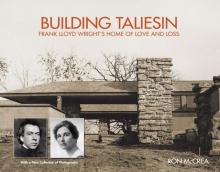

Building Taliesin

Building Taliesin