- Home

- Ron McCrea

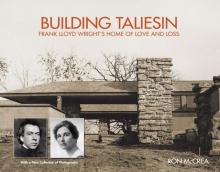

Building Taliesin Page 4

Building Taliesin Read online

Page 4

She added, “As near as I can find out he has only separated from her because he wishes to retain the beauty and ideality of their relationship and feared that by staying with her that he would grow to loathe her.”15

Fig. 20. Frank Lloyd Wright designed a townhouse in 1911 to be built on a narrow lot on Goethe Street, a fashionable address on Chicago’s near north side. It could have served as a winter residence and studio for the architect and Mamah Borthwick but was never built. Its features included skylights and a music balcony over the dining area. It has an exterior balcony on the gracious second level, known in Italy as the piano nobile.

That was hardly the truth. But if Wright dissembled about Mamah with Catherine, he lied openly to Darwin Martin. “The unfortunate woman in this case is making her way herself,” he wrote Martin on November 22. A week later, he told him: “I have left the woman you have in mind to make her future plans as though I were dead.”

Anthony Alofsin notes: “Wright was now obliged to lead a double life: a life of denying his love for Mamah Cheney while planning his future around her.”16

Eight weeks later he was back in Germany, having sailed aboard the Lusitania on about January 16, 1911. He needed to resolve issues with Ernst Wasmuth, his publisher, but those issues were settled by February 13. Wright stayed on through the end of March, and no doubt met again with Mamah.

Events leading to the establishment of Taliesin unfolded rapidly after his return. On April 3, he wrote to Darwin Martin requesting $10,000 to help his mother purchase property “up country” for “a small house.” On April 10, Anna signed the deed to purchase the Rieder property he had mentioned in Italy—next to the Porter farm, including a hill with commanding views of the Wisconsin River and the valley of his ancestors. The first plan of Taliesin was in Anna’s name. This deflected attention from Wright and protected the property from any legal claim by his wife. Site preparation began in the spring.17

Borthwick arrived in New York in June and paid a visit to the office of George Putnam, president of G. Putnam’s Sons, which would publish The Woman Movement. According to her letters, she then joined her children in Canada for the summer, perhaps with help from Lizzie. Mamah’s divorce was made final in Cook County Court on August 5, with Edwin claiming desertion. He remarried a year later, as soon as he could, and sent the children, John and Martha, with Lizzie to stay with Mamah at Taliesin in 1912 while he honeymooned in Europe.18 His new bride was Elsie Millor, whom Mamah described as Lizzie’s “dear friend.” Elsie and Edwin later had three children and moved to Missouri.

Mamah Borthwick, her maiden name now officially hers (she had begun to use it in Europe),19 came to her new home in Wisconsin in August. Wright called Taylor Woolley back from California on August 31 to work at Taliesin and provide Mamah with a familiar face. Wright divided his time between Taliesin and the remodeling of the Oak Park home and studio. He separated the property into two buildings, one for a home for Catherine and the children, the other for an income property for Catherine. The rental house was advertised in December. By that time, Wright had moved permanently to Taliesin. The one-year plan was complete.

Fig. 21. A 1910 postcard shows the Roman amphitheater and women tourists in the architectural park just off the main piazza in Fiesole. The amphitheater, built in the first century BCE, has been restored and is now used during summer festivals.

During the summer Wright had drawn plans for a four-story townhouse on Goethe Street in a fashionable neighborhood on Chicago’s near north side. It featured skylights and a music balcony overlooking the entertainment area, much like the one he built for Susan Lawrence Dana in Springfield, Illinois. In her first letter from Wisconsin, Borthwick told Key that Wright “has been building a summer house,” suggesting that a winter residence was also being considered. But the Goethe Street townhouse was never built. For the next three years, Taliesin was their home for all seasons.20

VILLA TALIESIN

In a letter from Italy to Charles Ashbee, Wright had described his situation lyrically. “I have been very busy here in this little eyrie on the brow of the mountain above Fiesole—overlooking the pink and white Florence, spreading in the valley of the Arno below—the whole fertile bosom of the earth seemingly lying in the drifting mists or shining clear and marvelous in this Italian sunshine—opalescent—iridescent.”21 Wright had discovered la bella vita—the beautiful life. Florence and Tuscany, with their lush gardens, good food, musical language, civilized manners, and folkloric as well as historic architecture, had given Wright a new feeling for organic living.

He looked at buildings and made drawings. Marie Sophie (Mascha) von Heiroth, a multilingual Russian pianist, and her husband, Alexander (Sasha), an actor and painter, shared the villa Fonte della Ginevra complex in Florence with Wright and the young men. When he moved to Fiesole they visited on Easter Sunday and he showed them drawings of houses inspired by Tuscan Villa traditions. Her grandson, Claes von Heiroth, notes, “He had especially studied Michelozzo’s Villa Medici in Fiesole.”22

That villa has been identified by several architectural authorities as a possible inspiration for Taliesin. Like Taliesin, it is terraced into the side of a hill, with the top garden level above the house and another below. It enjoys commanding views of the Arno River Valley and Florence. It dates from mid-fifteenth century, when Cosimo the Elder hired Michelozzo Michelozzi to design it for his son Giovanni dei Medici. Lorenzo the Magnificent inherited it in 1469, and the house gained fame as a gathering place for artists, writers, and philosophers.

Architectural writers say the Villa Medici was a departure from the castle-style villas built to defend rural landholders. It was an open and artistic “villa suburbana,” enjoying full communion with surrounding nature—gardens, pools of water, breezes, and the changing seasons.23 Taliesin would be like that.

In his introduction to the Wasmuth Portfolio, Wright shows how far he has come in his appreciation of Italian style. He has been privileged, he says, to be able to study the work of “that splendid group of Florentine sculptors and painters and architects, and the sculptor-painters and painter-sculptors who were also architects.” But greater than all these is the organic beauty of Tuscany’s “indigenous structures, the more humble buildings everywhere, which are to architecture what folklore is to literature or folk songs are to music.”

In these buildings, which do not reflect the religious piety of churches or the “cringing to temporal power” of palaces, one finds “the love of life which quietly and inevitably finds the right way.“

Wright continues: “Of this joy in living, there is greater proof in Italy than elsewhere. Buildings, pictures and sculpture seem to be born, like the flowers of the roadside, to sing themselves into being. Approached in the spirit of their conception, they inspire us with the very music of life.

“No really Italian building seems ill at ease in Italy. All are happily content with what ornament and color they carry, as naturally as the rocks and trees and garden slopes which are at one with them. Wherever the cypress rises, like the touch of a magician’s wand, it resolves all into a composition harmonious and complete.

“The secret of this ineffable charm … lies close to the earth. Like a handful of the moist, sweet earth itself, it is so simple that, to modern minds trained in intellectual gymnastics, it would seem unrelated to great purposes. It is so close that almost universally it is overlooked.”24

Here, in a few sentences, is the kernel of Wright’s manifesto for the natural house. Taliesin would be the first example to come from his hands.25

IN WRIGHT’S WORDS

In Exile

In ancient Fiesole, far above the romantic city of Cities in a little cream-white villa on the Via Verdi.

How many souls seeking release from real or fancied domestic woes have sheltered in Fiesole!

I, too, sought shelter there in companionship with her who, by force of rebellion as by way of Love, was then implicated with me.

Walking toge

ther up the road from Firenze to the older town, all along the way the sight and scent of roses, by day. Walking arm in arm, up the same old road at night. Listening to the nightingale in the deep shadows of the moonlit woods … trying to hear the songs in the deeps of life: Pilgrimages to reach the small solid door framed in the solid blank wall in the narrow Via Verdi itself. Entering, closing the medieval door on the world outside to find a wood fire burning in the small grate. Estero in her white apron, smilingly, waiting to surprise Signora and Signore with, ah—this time as usual the incomparable little dinner, the perfect roast fowl, mellow wine, the caramel custard—beyond all roasts or wine or caramels ever made. I remember.

Or out walking in the high-walled garden that lay alongside the cottage in the Florentine sun or arbored under climbing masses of yellow roses. I see the white cloth on the small stone table near the little fountain, beneath the clusters of yellow roses, set for two. Long walks along the waysides of the hills above, through the poppies, over the hill fields to Vallombrosa.

Back again, hand in hand, miles through the sun and dust of the ancient winding road, an old Italian road, along the stream. How old! And how thoroughly a road.

Together, tired out, sitting on benches in the galleries of Europe, saturated with plastic beauty. Beauty in buildings, beauty in sculpture, beauty in paintings until no “chiesa,” however rare, and no further beckoning work of human hands could draw or waylay us any more.

Faithful comrade!

A dream in realization ended?

No, a woven, a golden thread in the human pattern of the precious fabric that is Life: her life built into the house of Houses. So far as may be known—forever!

Fig. 22. Frank Lloyd Wright and Mamah Cheney dined at this table in the Villino Belvedere’s private garden in 1910. Wright writes of “the white cloth on the small stone table near the little fountain, beneath the clusters of yellow roses, set for two.” Photograph by Taylor Woolley.

THE RUSSIANS NEXT DOOR

During the winter of 1909–1910 Frank Lloyd Wright, his 19-year-old son Lloyd, and 25-year-old draftsman Taylor Woolley shared a building in Florence with a Russian family. As Lloyd recalled it, “The villino was divided into two parts opening from a tiny inner court. A charming Russian couple who played chamber music with their friends had one apartment and we enjoyed the cultured company.”26

The family included Alexander “Sasha” von Heiroth (also spelled Geirot), a painter; his wife, Marie Sophie “Mascha” von Heiroth (formerly Djakoffsky); and their little boy, Algar, who was not yet two. Mascha, beautiful and gifted, spoke six languages, played piano, and sat as a model for several famous artists, according to her grandson Claes von Heiroth, Algar’s son.27 She was married four times; Alexander was her third husband. They later divorced and he went on to act at Stanislawski’s Moscow Art Theatre and to appear in early Russian films. One was the 1914 silent production of Pushkin’s Mozart and Salieri directed by Viktor Tourjansky, in which he played Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.28 The play was later revived by Peter Shaffer as Amadeus. Algar grew up to become Finland’s ambassador to Mexico and Israel.

Fig. 23. The 1910 Florence air show was one of the first in Italy. On March 27 Enrico Rougier made the first flight over the city in a Voisin biplane.

Mascha kept a diary written in French. In 1910 she recorded a visit to the home of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mamah Borthwick, who had invited the whole family, including a nanny, to come up to their new rented home in Fiesole for Easter. Mascha was pleased, because the family was a month away from leaving Italy and it would be a last chance to see old friends and also visit Fiesole, where they had lived and had conceived Algar.

Fig. 24. Marie “Mascha” Djakoffsky von Heiroth (1871–1934) lived near Frank Lloyd Wright and Mamah Cheney in Fiesole in 1910 and kept a diary in French. Her grandson says she played piano and entertained often with her husband, Alexander von Heiroth (also spelled Geirot), a young artist who went on to act in Russian films. Frank Lloyd Wright bought one of his paintings. Mascha sold this portrait, painted in Finland in 1896 by Albert Edelfelt, to the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, where it hangs today.

DIARY ENTRY: MARCH 24, 1910

We are in an aviation craze! … People are talking of nothing but aviation, which will take place here for the first time. The show will take place on Easter Monday [March 28] at the Campo di Marte. Sasha will go see it; that sort of thing interests him a great deal. I would gladly go too, if someone would only offer a seat in the stands. Otherwise I won’t, because it’s too expensive, and if there is a huge crowd, I would rather not go.29

I’m beginning little by little to say my goodbyes! We are only here for one more month! … Sunday we are invited to the home of the architect Wright, who lived near us in the house of the woman who has a husband in Alaska. He has rented the magnificent Villa Belvedere in Fiesole and he invited the entire family there: Sasha, me, Algar, and the maid, as well as the two Halles. Thus it will be a pilgrimage on Easter Sunday and it will probably be our last visit to Fiesole. I would like Algar to see the place where he was conceived two and a half years ago.

Fig. 25. Mascha von Heiroth kept a diary in French.

DIARY ENTRY: APRIL 1, 1910

Our garden is all white with pear tree blossoms. On the wall behind the house climb the few flowers of the peach tree that our landlord intended to cut down because it does not bear fruit. I, who love it so much for the pretty Japanese pattern that it makes on the wall, did not allow it. I had the double windows taken off to replace them with green shutters the other day, since the nice weather continued. But since yesterday the Tramontana [northern wind] has been blowing, the mountains are once again all white with snow, and we fear that this weather is going to continue.

Last Sunday [March 27] we made our pilgrimage to the Wrights in Fiesole who received us quite well. They live in the charming little Villa Belvedere near our dear old Casa Ricci, with its lovely little garden and its impressive view of Florence. Algar misbehaved without bothering anyone since I brought the maid along with us to take care of him. After lunch, which we ate in a tiny dining room, I accompanied Sasha on Wright’s cello,30 then we looked at his extremely interesting drawings of houses, palaces, and churches, after which we went to the piazza.

Fig. 26. Alexander (Sasha) Von Heiroth, Gertrude Stein, Leo Stein, Marie (Mascha) Von Heiroth, Sarah Stein, and Harriet Lane Levy socialize at the Villa Bardi in Fiesole in 1908.

We stopped a moment at the Casa Ricci where the two elderly ladies Giuseppa and Filomena cried out joyfully on seeing us. Nothing had changed in the little garden. The same romantic clutter ruled as when we were there. No one lives there at present, but Leo and Gertrude Stein come back there for the month of July.31 So many good memories flashed before my eyes at the sight of this charming little spot. I would have liked to go everywhere I lived in Fiesole—to the Villa Bardi, and toward the lovely pine forest whence the superb road leads to Vincigliata, to Settignano—but time was running out. We had tea one more time on the Hotel Aurora’s terrace before taking the tram to the duomo. It was probably the last time I would see Fiesole!!

—Translation from the French by Jonah Hacker

Fig. 27. A fencing demonstration follows luncheon at the Villa Bardi in Fiesole in the summer of 1908. Alexander (Sasha) Von Heiroth, right, fences with Leo Stein, brother of Gertrude Stein. Sasha later had a career as a stage and film actor. Watching them are Allan Stein, 13, son of Michael and Sarah Stein; Gertrude Stein, grinning as she rests her head on the leg of Alice B. Toklas, her new love; Harriet Lane Levy, who traveled to Europe from San Francisco with Toklas but would lose her to Gertrude and return home alone; Maria (Mascha) Von Heiroth; and Sarah Stein, Allan’s mother (behind Sasha’s sleeve). Pablo Picasso painted a portrait of Allan in 1906. Michael Stein, Allan’s father and Gertude’s brother, is the likely photographer. Photos from Mascha’s albums are courtesy of Claes Von Heiroth.

NOTES

1. Frank Lloyd

Wright to Darwin Martin, quoted in Roger Friedland and Harold Zellman, The Fellowship (New York: HarperCollins, 2006). The authors credit the SUNY-Buffalo University Archive as their source. I use Borthwick as Mamah’s surname because that was her practice in Europe and afterward. Wright mentions Mamah leaving Edwin Cheney in June 1909 in a letter to Anna Lloyd Wright dated July 4, 1910, © Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ. This letter was first mentioned by Filippo Fici in “Frank Lloyd Wright in Florence and Fiesole, 1909–1910,” Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, vol. 22 no. 4 (Fall 2011). The author is grateful to Fici for receiving him at his studio and providing helpful information about Florence in 2004 and again in 2011 and 2012. The chronology for this chapter relies in part on Fici’s article; the record established by Anthony Alofsin in Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910–1922 (Chicago, 1993), 307–309 and Neil Levine in The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright (Princeton, 1996), Ch. III–IV; and the letters of Mamah Borthwick to Ellen Key, Ellen Key Archive, Royal Library of Sweden. The author visited Fiesole in May, 2004, and the descriptions are direct reporting.

2. An English adaptation of the Wasmuth Portfolio is Frank Lloyd Wright, Drawings and Plans of Frank Lloyd Wright: The Early Period (1893–1909) (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1983).

3. Frank Lloyd Wright to Anna Lloyd Wright, July 4, 1910.

4. Frank Lloyd Wright Wright to Taylor Woolley, June 16, 1910, Taylor Woolley Manuscript Collection, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah. The information about Lloyd’s travels is from Fici, “Frank Lloyd Wright in Florence.”

5. Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography (1932), reprinted in Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, v. 2, Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, ed. New York: Rizzoli International, 1992, 220. Wright’s spelling of the female servant’s name as Estero is questionable. Esther in Italian is Ester.

Building Taliesin

Building Taliesin