- Home

- Ron McCrea

Building Taliesin Page 6

Building Taliesin Read online

Page 6

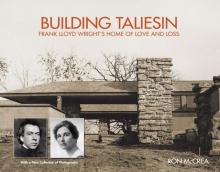

Fig. 40. Richard Lloyd Jones sits at his publisher’s desk at the Wisconsin State Journal in Madison. He bought the capital city daily from the father of Thornton Wilder in July 1911 with financial help arranged by “Fighting Bob” La Follette.

WHO WERE PROGRESSIVES?

The Progressives were largely members of the educated middle class—what one writer calls “the radical center.”12 They sought to address the ills of a newly industrializing society by finding a middle way between the big-business establishment and the nationalizing socialists. They supported private property, farm and home ownership, and small business but favored public ownership of banks and utilities and wanted the state to serve as the public’s referee, regulator, equalizer, and protector.

University of Wisconsin economist Richard T. Ely spoke for many Progressives when he said, “The balance between private and public enterprise is menaced by socialism on the one hand and by plutocracy on the other.”13

After the Civil War most of the political action in Wisconsin was within the Republican Party—the Party of Lincoln. The Progressives comprised the liberal wing and the conservative Republicans called themselves Stalwarts. The Democratic Party, still tainted as the party of secession, was a weak factor, with less power than the socialists, who had become a rising force in German Milwaukee.14

Figs. 41 and 42 Frank Lloyd Wright took these portraits of his aunts, the co-founders of Hillside Home School, in 1898. Jane Lloyd Jones (Aunt Jennie), left, and Ellen Lloyd Jones (Aunt Nell), right, were early progressive educators who organized a coeducational school for children of the big Welsh clan. It soon grew into a boarding school that enrolled many from Chicago.

PROGRESSIVE INSTITUTIONS: TOWER HILL

The Republican Party was founded in Ripon, Wisconsin, in 1854 by a group opposing the extension of slavery to the new states of the West. It ran Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860, and after the Civil War the words “Lincoln,” “Union,” and “Unity” became watchwords for one veteran of the Grand Army of the Republic, Reverend Jenkin Lloyd Jones.

Fig. 43. Hillside Home School, seen here circa 1910, was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright for his aunts in 1901. He designed their first building at age 19.

Fig. 44. Wright did the lettering for the envelope containing a packet of photos he prepared to help advertise his aunts’ Hillside Home School in 1900. The three-pronged red figure is the Welsh rune signifying the Lloyd Jones motto, “Truth Against the World.”

“Jenk,” the last child of Richard and Mallie to be born in Wales, served as a Union Army artilleryman in the war, fighting in the battles of Vicksburg, Missionary Ridge, Chattanooga, Lookout Mountain, and Atlanta and suffering a broken foot at Missionary Ridge that required him to walk with a cane.15 He emerged an evangelical pacifist and advocate of reconciliation—of races, of religions, of men and women. His weekly magazine for the Western Unitarian Conference was called Unity.

He based himself on Chicago’s South Side, building the Abraham Lincoln Center for social services and outreach and founding an interfaith, interracial church called All Souls. Jenk was an ally of Jane Addams and Hull house, where Wright’s mother and sister both volunteered, and he created a summer camp near Janesville, Wisconsin, much like Addams’s fresh-air camps for city children.16

In 1889 he established Tower Hill, a Wisconsin summer campground and conference center that drew campers and speakers from Madison, Chicago, and beyond. Together with Hillside Home School, the pioneering coeducational boarding school run by Ellen and Jane Lloyd Jones, it made Jones Valley a vital center of Progressive discussion and liberal preaching, and a summer staging area for the La Follette political movement.

Jones purchased the 60-acre Tower Hill property, which included a former lead-shot ammunition-making tower over the Wisconsin River, for $1 an acre. The retreat grew to include 25 cottages, the Emerson Pavilion dining and meeting hall, and other structures. The big event was the end-of-season Grove Meeting held the second weekend in August. One of those Chautauquas was in progress in 1914 when Taliesin was destroyed.17

Fig. 45. Wright photographed boys and girls learning to sew. Hillside was one of the first coeducational boarding schools in the country.

In 1906, Jenk invited the Wisconsin Federation of Women’s Clubs to use Tower Hill for its annual Women’s Congress, and it became an annual event to advance women’s rights—another strand of the Progressive movement. One of its two leading organizers was novelist, dramatist, and suffragist Zona Gale.

La Follette Day was also a regular Tower Hill event, held in honor of “Fighting Bob.” “The Emerson Pavilion was packed when public assemblies were held,” Wright’s sister Jane Porter remembered. “Robert La Follette Sr. spoke in the pavilion many times to groups far too large for the space.”18

PROGRESSIVE INSTITUTIONS: HILLSIDE

When La Follette left for Washington in January 1906 to take his seat in the Senate, he and his wife, Belle Case La Follette, enrolled their three youngest children at Hillside Home School.

The Dodgeville Chronicle reported on February 2: “About seventy members of the Hillside School enjoyed a sleigh ride to this city Wednesday and the keys of the city were turned over to them for the day. The hardware and notion stores were the first visited, where they secured all the tin horns in stock and thereafter their presence in the city was known to every citizen. A visit was made to our new high school, which was very enjoyable to the members of both schools.

“The students and teachers were accompanied by James Lloyd Jones and the principal, Miss Ellen C. Lloyd Jones, Miss Jane Lloyd Jones and Miss Annie Lloyd Wright [Wright’s mother]. Among the visiting students were Robert, Philip and Mary La Follette, children of Senator and Mrs. R.M. La Follette.”19

Robert “Young Bob” La Follette Jr. (1895–1953) went on to take his father’s seat in the U.S. Senate and become an architect of the New Deal. He was unseated by Joseph McCarthy in 1946.

Philip F. “Phil” La Follette (1897–1965) went on to become the governor of Wisconsin who bravely led the state through the Depression. He also played a key role in Frank Lloyd Wright’s fortunes, serving as his lawyer, negotiator, and financial adviser.20

Hillside home School was initially organized to educate the growing Lloyd Jones brood. The aunts, both leaders in institutions outside Madison, returned to build a residential school on the late patriarch Richard’s farmstead. Wright designed the shingle-style building, which he called a product of “amateur me,” at age 19. In 1901 he expanded it with a fully modern building. The school, Nell and Jenny said, would operate according to “the principles of Emerson, Herbert Spencer, Froebel and other exponents of ‘The New Education.’”21

Fig. 46. Boys play football in a Wright photograph taken in autumn.

JENKIN’S CREED, 1913

On November 6, 1913, Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones celebrated his 31st anniversary as the founder of All Souls Church in Chicago. The chicago Tribune printed this statement:

“During the last thirty-one years I have been a pastor in chicago. I have stood for that communion of religion that refuses to be rimmed to any ‘Christian’ name or interpretation. Jew, Buddhist, Mohammedan are eligible for the fellowship of the church I have tried to build.

“I have tried to interpret religion as the reconciling force of society, the bond that holds man to man and man to his duty when all other bonds fail.

“I have stood for religion unrimmed by creeds.

“I have stood for religion that stands for progress, freedom and brotherhood.

“I have, through all these years, stood for the application of religion.

“I have stood for rights of women as an equal partner to men.

“I have stood for the rights of the colored man as eligible to all the privileges of this church and whatever privileges civilization had to give a soul when it is made worthy by effort, sanity, sobriety and purity.”

It had a strong teacher-to-student ratio and, as it grew to include more

urban children from Chicago, was described by the aunts as “a home-farm school, removed from the excitements and distractions of the city.”

“Character building is its aim. Its method, so far as possible, is to make the pupil self-regulating. It is the province of the teacher to guide rather than to drive, to help rather than to substitute,” they wrote.22

Hillside earned such a strong reputation that its graduates were admitted virtually upon application to the University of Wisconsin, the University of Chicago, and Smith and Wellesley colleges.

The La Follette children were not the only stars it produced. Wright’s sister Maginel and his sons Lloyd and John became noted artists and architects. Florence Fifer Bohrer, daughter of the Illinois attorney general and later governor, became the first woman to be elected to the Illinois State Senate.

Fig. 47. Girls play basketball at Hillside Home School in a Wright photograph.

In a tender memoir about her days at the school—which included having an African American roommate—Bohrer remembered a visit from “Fighting Bob.”

“While I was much interested at the time, I do not recall what Mr. La Follette talked about,” she wrote. “It was all exciting, and I remember that the Uncles were enthusiastically supporting his candidacy for office… . There was much talk of La Follette’s courage and independence. He had formulated a reform program and was appealing directly to the people.”23

REVOLUTION IN MADISON

The summer of 1911—Taliesin’s first summer—was the high-water mark of Progressivism in Wisconsin. In Milwaukee, the Social Democrats under Emil Seidel were building on their 1910 electoral sweep, creating the parks, sanitary systems, and other public works that would give them the name “sewer socialists.” Victor Berger became the first Socialist ever elected to Congress.

In Madison, Governor Francis McGovern and the Progressive majority, responding to the public’s appetite for change and sensing that “the only way to beat the Socialists is to beat them to it,” went full steam ahead on an ambitious legislative agenda.24 When they adjourned on July 15, 1911, they had passed the largest body of legislation ever approved in a single session in Wisconsin: 664 bills. Virtually all became law.25

The reforms included the nation’s first workmen’s compensation program, the first successful progressive income tax, restrictions on child labor and women’s labor, a teacher’s pension system, a state “public option” life insurance program, the beginnings of a German-style state vocational system, the exemption of cooperatives from antitrust laws, home rule for cities, a “corrupt practices” act placing tight limits on campaign spending, and establishment of the right of citizens to recall elected officials and create laws by referendum.

It was, in the words of a university political scientist at the time, “the most constructive program of popular government and industrial legislation ever presented to any state.” the political reforms, he said, would “establish a line of vision as direct as possible between the people and the expression of their will.”26

Women’s will would not be expressed, however: The Legislature approved a bill giving women the right to vote but referred it to a public referendum in 1912 (in which women would have no vote) rather than sending it directly to the governor for his signature. The referendum failed, owing largely to opposition from Milwaukee’s brewing companies and the state’s barley growers, who smelled Prohibition in the air. Temperance was a powerful theme in both the Progressive and feminist movements, and in the Lloyd Jones family.27

As a result of the 1911 session, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mamah Bouton Borthwick would be among the first citizens to pay a progressive income tax; but only he would have the right to vote.

WISCONSIN IDEAS

The University of Wisconsin played a key role in developing the landmark program of the 1911 Legislature, and Lloyd Joneses were among the university’s leaders. La Follette and his Capitol bill-writing shop, the Legislative Reference Bureau, had crafted a unique working relationship with the University of Wisconsin called “the Wisconsin Idea.” The idea was that the university would serve as the state’s full partner in policy research, development, and experimentation. It would leave the ivory tower and roll up its sleeves to plan and implement state improvements ranging from railroad property valuation to showing young farmers how to select the best breeds and seeds.

Fig. 48. Boys and girls are photographed by Frank Lloyd Wright in their classroom. Froebel-type blocks and a globe are in the foreground.

Its motto was, “The boundaries of the University are the boundaries of the state.” This meant, said Frederic Howe in 1912, that “the university is a great nerve center, out from which influences radiate into every township in the state. No locality is so obscure that it is not touched by these forces, and no citizen is so poor that he cannot avail himself of some of its offerings.”28

During this heady time, two uncles of the Lloyd Jones family were named Regents of the university by La Follette’s hand-picked successor, Governor James O. Davidson. James Lloyd Jones served on the Board of Regents from 1906 until his death in 1907. Enos Lloyd Jones succeeded him and was still on the board when the 1911 Legislature finished its marathon session.29

EDITOR AND PUBLISHER

“Fighting Bob” La Follette wanted “a powerful progressive daily newspaper at Wisconsin’s capital—something to complement his recently launched La Follette’s Weekly Magazine, the medium he selected to advance his political philosophy on a national level.”30 On July 29, 1911, just after the Legislature adjourned, he facilitated the purchase of the daily and Sunday Wisconsin State Journal by Richard Lloyd Jones. Richard, 38, was Jenk’s son and Wright’s cousin.

Wealthy friends of La Follette loaned Jones, who had returned from New York and Collier’s magazine, $85,000 of the $100,000 he needed to buy the paper from Amos Wilder. Wilder, a former diplomat, was the father of Pulitzer Prize-winning dramatist and novelist Thornton Wilder.31

“Between July 1911 and July 1919 the ‘virile pen and militant personality’ of Richard Lloyd Jones made the Journal a powerful voice for the Progressive movement in Madison and around the state,” Madison historian david Mollenhoff writes. “In 1912 it carried La Follette’s presidential banner. Naturally, Jones pushed La Follette ideals including labor legislation, academic freedom, women’s suffrage, and black rights, while decrying child labor, big business, and government corruption.”32

Jones also made space in the paper for a regular column by Belle Case La Follette,33 and would endorse Frank Lloyd Wright’s design for a downtown hotel in 1912. The State Journal’s circulation doubled in the first year Jones owned it. His style was something new in Madison journalism, Mollenhoff notes: “Unlike many journalists who gave both sides of an issue so that readers could draw their own conclusions, Jones told his readers what was right and never let them forget it.”34 That also could describe the style of Frank Lloyd Wright.

MAKING ROOM FOR FRANK AND MAMAH

Temperamentally and in most other ways, Wright should have been a natural fit for Jones Valley in 1911. He had been a known quantity there for 30 years, had designed buildings for his aunts and sister, and brought with him an international reputation as a visionary architect with a track record of 100 buildings built and 50 others planned in the previous decade.

He knew the valley; shared the Unitarian regard for Emerson, Whitman, and the other transcendentalists; was intensely musical; had his own Froebel training; and had sent several of his own children to Hillside for schooling. His sister Jane and her husband lived nearby and his mother was a regular visitor. Wright had hired dozens of local laborers and craftsmen to build Taliesin, and claimed in his first interview with the Dodgeville Chronicle that he would be employing several draftsmen to handle “a half a million dollars’ worth of work now in hand.”35 He had strong ties to Madison, where he spent his teenage years and would design buildings in every decade of his long career. In 1911 a project for a new down-town hotel was on the bo

ards.

Fig. 49. Jane Wright Porter, Frank’s sister, taught at Hillside and organized the Lend-a-Hand Club for women. She and Zona Gale led the effort to build a women’s clubhouse in 1914. Wright designed Tanyderi for her and her husband Andrew in 1907. The photo is from 1922.

Like the Lloyd Joneses, he had ties to Progressive Chicago. Jenk’s friend Jane Addams gave him Hull House as his platform when he delivered his seminal defense of mass-produced building materials, “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” in 1901. He knew the movers of the Chicago Renaissance arts revolt, including Margaret Anderson, founder of The Little Review; Harriet Monroe, founder of Poetry; and Maurice Browne, founder of the Little Theater, who eventually connected him with Aline Barnsdall and a career in Los Angeles.36 (Carl Sandburg, the poet who became a great Chicago friend, was serving as secretary to the socialist mayor of Milwaukee in 1911.)

Fig. 50. Wright’s photograph of a chemistry class at Hillside shows girls receiving science training and, on the right, a student who could be African American.

Mamah Bouton Borthwick likewise could have been expected to fit into the family culture of the Valley. She was well-educated, with a master’s degree from Michigan, and spoke several languages. She had participated in the intellectual life of Oak Park, making presentations—including one on Robert Browning with Catherine Wright—to the Nineteenth-Century Women’s Club, which Anna Lloyd Wright had co-founded.

Building Taliesin

Building Taliesin